Is human creativity fading away?

It's time to confront the creativity crisis gripping our species

Dr. Kyung Hee Kim - known as K to her American friends - was the first female from her Korean village to attend high school.

She went on to complete a PhD in Korea, before completing a second in the US. Her supervisor was Ellis Paul Torrance, a man long hailed as “the father of creativity”.

In 2010 - seven years after Torrance died - Dr. Kim published a paper that made the front page of Newsweek.

In the paper, Dr. Kim analysed creative thinking test scores since the 1960s for nearly 300,000 Americans, from age 3 upwards.

The key takeaway? Since 1990, even as IQ scores had gone up, creative thinking scores had gone backwards. Big time.

This post is my attempt to make sense of this troubling discovery, and it’s a search for signs of creativity in crisis elsewhere. Are things really so bad, or is human creativity flourishing like never before? Where are humans really at, creativity-wise? We’ll look at the data, and we’ll interrogate the vibes.

Before we get into it, here’s some quick context for Dr. Kim’s research…

The Torrance Tests

The Torrance Tests have been in use since the 1960s.

Torrance, a giant in the field of creativity research, drew on J.P. Guilford's work around divergent thinking for the tests.

💡💡💡 Divergent thinking is a mode of creative thought that’s all about breadth of ideas; exploring lots of options before you narrow them down.

In Guilford’s model, there are eight dimensions of divergent thinking (covered in these slides from a skill-share I ran on this topic at my old job).

Of those eight, the Torrance Tests focus on fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration.

There have been some criticisms of the Torrance tests, like this paper which has been refuted by Dr. Kim. And of course, there will always be aspects of creativity that are domain-specific or transcend measurement altogether, but the Torrance Tests remain the most widely-used and validated divergent thinking tests decades after their introduction.

As reported in that Newsweek feature:

“Nobody would argue that Torrance's tasks… measure creativity perfectly. What's shocking is how incredibly well Torrance's creativity index [predicts] kids' creative accomplishments as adults.”

You can read more about the kind of tasks involved in the tests here.

Why did the scores drop?

In her research, Dr. Kim found that:

Fluency scores dropped from 1990 to 2008.

Originality scores dropped from 1990 to 1998, and remained static from 1998 to 2008.

Elaboration scores dropped from 1984 to 2008.

In the paper, she offers some commentary on why creativity has declined whilst IQ scores have improved:

“Children have ever increasing opportunities for knowledge gathering and study… but to be creative, they also need opportunities to engage in the mental process of building knowledge through mental actions.”

Think this is a recent problem? All the way back in 1846, the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard (“father of existentialism” and expert on human despair) was warning about the consequences of such a narrow approach to education:

“There are handbooks for everything, and very soon education, all the world over, will consist in learning a greater or lesser number of comments by heart, and people will excel according to their capacity for singling out the various facts like a printer singling out the letters, but completely ignorant of the meaning of anything.”

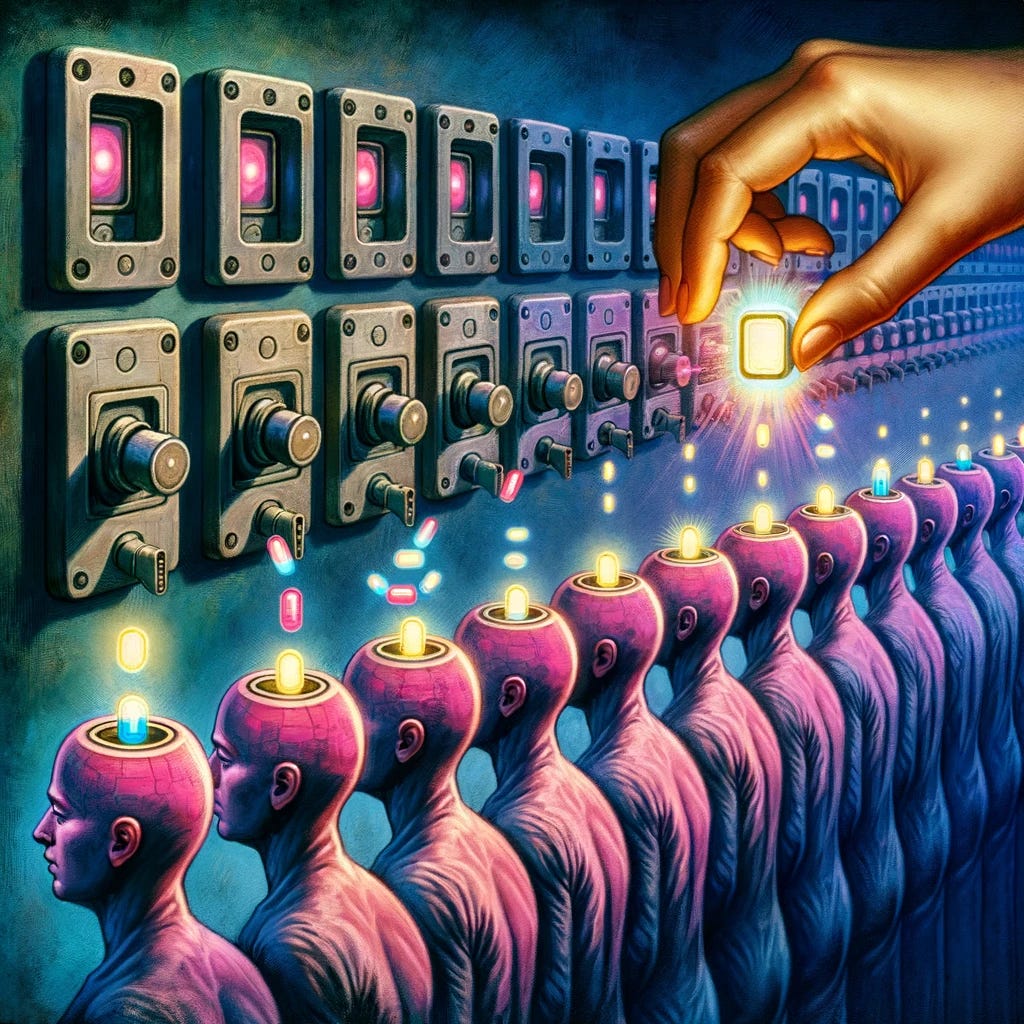

The issues go beyond the classroom. Drawing on other academics’ work, Dr. Kim suggests that:

“Free, uninterrupted time for children should be restored on school and home schedules… However, over the past few decades the amount of free play for children has reduced. Hurried lifestyles and a focus on academics and enrichment activities have led to over-scheduling structured activities and academic-focused programs, at the expense of playtime. Children also spend ever-increasing amounts of their days interacting with electronic entertainment devices.”

She continues:

“Also lost in the rush to provide ever more stimuli and opportunities to children is time for adults to listen to their children. Parents and teachers must personally provide receptive, accepting, and engaged psychological support to encourage creativity. A child needs meaningful interactions and collaborations to be creative.”

So there’s the expert diagnosis - the loss of our creative capacities begins in childhood, caused by packed schedules, overstimulation, not enough high-quality human interaction, and fewer opportunities to play.

Is this just a US problem?

That seems unlikely; Dr. Kim has argued elsewhere that “the US school environment fosters more creativity in students than other countries, including the UK.” And creative subjects are in decline at school and university level in the UK.

Torrance Test scores also declined for 8-12-year-olds in Sudan between 2005 and 2018.

And how’s this for another signal? In 2019, 72% of British nursery workers surveyed said fewer children have imaginary friends than five years earlier. 63% of those questioned said they think screens are making children less imaginative.

Children’s home and school environments are stifling the expression of their creative potential. That seems pretty clear. But what’s going on in the wider world? What kind of creative nourishment is our culture providing? And how is the creativity crisis manifesting beyond Torrance Test scores?

Let’s take a look…

Creative desolation in wider contemporary life

First, we’ll consider pop culture. Then, the state of advertising. And after that, we’ll seek out signals from science and check the creative pulse of patents being filed.

Formulas, nostalgia, and the death of counter-culture

What signals can we discern from the landscape and language of mass-market creative production? How tangy is the liquid we’re all pickling in?

In his widely-cited article The age of average, Alex Murrell convincingly shows that:

“From film to fashion and architecture to advertising, creative fields have become dominated and defined by convention and cliché.”

I’d recommend reading his article in full, and lingering on its bleak visual collages of the bland uniformity that’s colonised so many domains.

Jesse Armstrong (Peep Show, Succession) describes how “the tech-led streamers… are on the verge of blanding out TV into a grey globalised goo.”

This cultural flatness - this distinct absence of tang - is perhaps both a symptom of creative decline, and a cause of its continuation.

As Adam Mastroianni argues (supported by a whole bunch of data and graphs):

“Movies, TV, music, books, and video games should expand our consciousness, jumpstart our imaginations, and introduce us to new worlds and stories and feelings. They should alienate us sometimes, or make us mad, or make us think. But they can’t do any of that if they only feed us sequels and spinoffs. It’s like eating macaroni and cheese every single night forever.”

His analysis shows that:

“Until the year 2000, about 25% of top-grossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, remakes, reboots, or cinematic universe expansions. Since 2010, it’s been over 50% every year. In recent years, it’s been close to 100%.”

In his article The Narco-Image, John Menick also compares mainstream cinematic output with mass-produced foods, where manufacturers seek the sweet-spot of, say, a donut that’s not so sugary that you don’t come back for more. He explains:

“The field’s early lessons in what it calls “sensory-specific satiety” were learned in the American military, when researchers tried to get soldiers to eat more of their rations… If the rations were too bland, soldiers would not eat them. But if they tasted too strong, soldiers would often tire of the strong taste after several meals… The food industry that grew out of military food science understood that food should taste intense enough to give pleasure and stand out from the competition, but not so intense as to satisfy completely.”

In Menick’s words, “to feel nothing, enjoy nothing, experience nothing as new or novel — these are the logical and distant ends of the narco-image.”

In 2012, closer to the publication of Dr. Kim’s paper, Kurt Andersen explored these themes in an article for Vanity Fair. He challenges readers to identify the “big, obvious, defining differences” between pop culture in 2012 and 1992, and concludes:

“Movies and literature and music have never changed less over a 20-year period. Lady Gaga has replaced Madonna, Adele has replaced Mariah Carey — both distinctions without a real difference — and Jay-Z [is still Jay-Z].”

11 years later, those artists all remain popular. Adele has 54.5 million monthly listeners on Spotify. Madonna has 37.6m. Jay-Z has 35.7m. Mariah Carey has 26.8m.

They’re all eclipsed by Taylor Swift, admittedly (103.5m), but even her latest release is a remake. A remake of an album with a title that points us nostalgically back in time, and with a repackaged 80s synth-pop sound.

Research by Colin Morris, based on 15,000 songs from 1958 to 2017, shows that pop lyrics are getting more and more repetitive. Chord structures in music have been getting more similar since the mid-80s too.

Andersen points to a beguiling paradox:

“Ironically, new technology has reinforced the nostalgic cultural gaze: now that we have instant universal access to every old image and recorded sound, the future has arrived and it's all about dreaming of the past.”

How extra-prescient this seems in our brave new generative AI age, where the inherent remixiness of all creative action has been amplified ad absurdum.

Surveying the vitality of our shared symbolic world, it’s hard not to see evidence of unimaginativeness everywhere. A stark cycle of creative disengagement, where familiar ideas breed unadventurous appetites and the empty novelty of endlessly scrolling social feeds stops us hungering for something more.

Of course, there’s always been a middle-of-the-roadness to mainstream culture, but once upon a time this was offset by counter-cultural movements always threatening to subvert and destabilise the centre ground.

“These days, people get into music to be part of the establishment… There’s no counter culture – only over-the-counter culture.”

As Eaon Pritchard argues, millennials (like me) are “the first generation that was unable to come up with any kind of counter-culture idea that their parents would be afraid of.” Damn.

For Carolina Busta, the radical energy of the subcultures that remain is rendered inert by the dynamics of 21st-century techno-capitalism:

“What logic could possibly be upended by punks, goths, gabbers, or neo-pagans when the internet, a massively lucrative space of capitalisation, profits off the personal expression and political conflict of its users?”

Bringing us back to food-as-metaphor, Cameron Summers proposes that “these identities, if they can even be called that are commodities. They are, from a cultural sense, predigested.”

The creative crisis in advertising

In 2019, Peter Field (a major figure in advertising effectiveness) published a report for the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising titled The Crisis in Creative Effectiveness. He showed that the profitability of creatively-awarded campaigns had been in decline for a decade, and pointed to awards judges favouring “short-term ‘disposable’ creativity” over long-term, memorable campaigns based on big, bold, fame-worthy ideas.

Here’s how Arwa Mahdawi summed up the state of advertising in an article published in 2022:

“The creativity that used to define advertising has been slowly seeping out of the industry. Marketing has got less wacky and weird and become way more corporate and safe. A lot of ads look and feel the same.”

She adds:

“Advertisers want to be creative but they also don’t want to get in trouble for being too out there. So they just end up doing what everyone else is doing and a downward spiral of creativity – and effectiveness – follows.”

Orlando Wood, author of Lemon: How the Advertising Brain Turned Sour, argues that most ads now just aren’t very interesting “unless you're in the market for the product or you’ve already been primed to like the brand.” Wood draws on Iain McGilchrist’s work on the hemispheric functioning of the brain to explain how this has come to pass - we’ll come back to that shortly.

It’s worth adding that plenty of people in the world of advertising think we’ve never been in a more creatively exciting time, with stupidly powerful tools for realising ideas, and more platforms than ever to play with. It’s also easy to lapse into rose-tinted reflection about how much better advertising used to be, when of course we remember the hits more than the misses.

But, along with the effectiveness evidence, consider these stats:

Only 17% of consumers think typical TV ads are memorable (source)

Only 12% think typical social ads are funny (source)

42.7% of internet users worldwide use ad blockers (source)

What we’re being served through our screens and audio devices, whether it’s entertainment or advertising, is overwhelmingly forgettable. Sure, there are still some genuine gems that I can just about imagine being spoken about 50 years from now, but they’re increasingly easy to miss amidst the unending avalanche of mediocrity.

Perhaps all this analysis of culture and advertising feels trivial compared to the bigger questions of human progress that Dr. Kim’s findings evoke. What does the creativity crisis mean for science, innovation, and our species’ long-term survival prospects? Is there some hope to be found in these domains? I wish I had better news for you…

Creative stagnation in science and innovation

Aakash Kalyani is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, with research interests in economic growth and innovation. In 2022, he published a paper titled The Creativity Decline: Evidence from US Patents. By measuring the occurrence of two-word combinations that didn’t appear in previous patents, he shows that “the creativity embodied in US patents has dropped dramatically over time”. Even as “the overall number of patents per capita have almost tripled over the last three decades, average patent creativity… has halved.”

In 2023, Michael Park, Erin Leahey & Russell J. Funk (great name) published a paper in Nature titled Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. They found that, contrary to the expectation that accumulating more knowledge opens up ever more avenues for creative exploration, “papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions.” They observed this pattern “universally across fields” and found it to be “robust across multiple different citation- and text-based metrics.” They blame this trend on a “narrowing in the use of previous knowledge” and conclude that “slowing rates of disruption may reflect a fundamental shift in the nature of science and technology.”

A popular hypothesis here is that all the “low-hanging fruit” has already been picked. The authors refute this idea, as does Adam Mastroianni in his beautifully-headlined post Ideas aren’t getting harder to find and anyone who tells you otherwise is a coward and I will fight them.

A key problem, it seems, is that people doing science and innovation work are increasingly “less likely to connect disparate areas of knowledge”. If you accept, as Steve Jobs once asserted, that “creativity is just connecting things”, this is a big problem.

“In an extreme view the world can be seen only as connections, nothing else.”

Tim Berners-Lee, Weaving the Web

The extinguishing of “lantern consciousness”

The American philosopher-psychologist Alison Gopnik has written several books on how babies learn. One of her stickiest concepts is the idea of two fundamental modes of human consciousness:

Lantern consciousness, where all stimuli are taken in from all directions without much editing

Spotlight consciousness, where the body-mind zeroes in on the information or task at hand

The lantern mode is the natural state for babies, but consciousness narrows as we age - “as we know more, we see less.” By contrast, going to the shop with an infant is “like going to get a quart of milk with William Blake.”

As adults, we can still access the more diffuse lantern mode, which “lends itself to mind-wandering, free association, and the making of novel connections.” But it seems we’ve largely forgotten how.

It’s worth reflecting on how, as a species, we’ve come to privilege the narrower forms of attention and thought that seem to be stifling science and perpetuating media monotony.

Since the Enlightenment, the West has existed in a condition you might call rampant rationalism - a world, as I described it in an article for MediaCat, “where data rules, where ‘true‘ means testable”.

We rely on simplified models of the world. These models are incredibly useful - they help us understand and manipulate our surroundings. As the writer and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist notes, “since the Industrial Revolution we’ve become masters of doing this.” But we also overestimate “our ability to predict and understand and control things,” he says - we’ve lost touch with “subtle, more complex ways of seeing the world”.

McGilchrist uses the distinct (but interdependent) roles of the two hemispheres of the human brain as a lens for exploring this shift. In his 2009 book, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, he shows how the differences between the two sides of the brain are more important than recent scientific discourse would suggest, and that, as a culture, we’ve long been engaging with the world in a left-brain-dominant way.

To massively oversimplify:

The left-brain reduces things to their parts, and seeks to fit things into categories it already knows

The right-brain appreciates the wholeness of things, and makes space for context, connections, relationships, and novelty

The left-brain is the spotlight. The right-brain is the lantern.

In the book, McGilchrist explains that:

“The left hemisphere needs certainty and needs to be right. The right hemisphere makes it possible to hold several ambiguous possibilities in suspension together without premature closure on one outcome.”

There’s nothing inherently wrong with the left-brain’s narrow agenda. Indeed, as McGilchrist stresses, “our talent for division, for seeing the parts, is of staggering importance.” The “gifts of the left hemisphere have helped us achieve nothing less than civilisation itself,” he says. But “alone they are destructive. And right now they may be bringing us close to forfeiting the civilisation they helped to create.”

Remember what our friend Kierkegaard had to say about where education was going wrong? McGilchrist has a similar view:

“We don’t insert understanding into people like we insert a widget into a machine. We draw it out, which is actually the metaphor behind the word education. We bring out things that are latent in people, we seem to have lost that… now there is a host of well-meaning restrictions and rules and algorithms and procedures and tick boxes and so on which just basically destroy the meaning of education.”

In short, he laments in another interview, “we've taken the universe apart, and… have no idea how to put it together again.”

That final statement feels a bit too defeatist to me. There’s lots we know about how early life could be different, and how we can reclaim our creativity - and our wholeness - as adults. The world feels ripe for a reintegration of the right-brain’s blessings. The voices against the industrialisation of education, the flattening of culture, and the hyper-specialisation of science are growing in volume. Despite the major challenges, there are sources of hope, and new paths begging to be explored.

In a follow-up to this post, we’ll look at the way forward. We’ll marvel at the power of play, wonder at the need for chaos, reflect on the role of quiet, and consider the potential of “mindapps” like mindfulness and psychedelics in the creative renaissance so many of us crave.

Take a trip to Thinkytown

This edition of Weirdness Wins is sponsored by Ideas On Acid®.

Ideas On Acid is a forthcoming card deck by ME!

It’s a set of 50 imagination-enhancing, idea-generating practices for adventurous thinkers like YOU.

Interested?

Ohh shit man, you just nailed it articulately what I have been perceiving for an age.

This afternoon I had my first conversation with a near neighbour whose ventures ( professional and social) are in the musical sphere. For context, he's mid twenties and I'm close to 60, anyway as we ( well, mainly me) dropped enquiring questions to the other in an attempt to put some colours on a blank persona. I asked him for his perspective on the view that culturally we are less creative than prior. Ha, he didn't like that and firmly rebutted the notion, and there lies the problem. Anyway, all wasn't lost as I was inspired to see what others had to say, and here we are.........

Wow! This is brilliant and touches on so many things that many are feeling.