Play as a portal to everything that matters most

Human creativity is in decline. Without play, we're doomed.

“Play is the foundation of learning, creativity, self-expression, and constructive problem-solving.”

Susan Linn, writer, psychologist, ventriloquist, and children’s advocate

“This is the real secret of life — to be completely engaged with what you are doing in the here and now. And instead of calling it work, realise it is play.”

Alan Watts, philosopher

“The creative adult is the child who has survived.”

Ursula K. Le Guin, author

Why don’t we worship play? Why, in so many ways, are we erasing play from the human experience? And what might we begin doing differently?

Welcome to the first essay in my Creative Renaissance series, where we’ll explore five key portals to a more creative, more human future.

Today’s topic is play. Let’s begin by looking at how childhood play has changed over the last 50 years…

From rough and tumble to Roblox and TikTok

Did you know the number of adventure playgrounds in England was cut in half between 1980 and 2021, according to research commissioned by Play England? Alice Ferguson, director at the charity Playing Out, says “children’s lives have become incredibly restricted, indoors, isolated and inactive, largely due to changes in the outdoor environment.” In the US, children now spend half as much time in unstructured outdoor activities compared to the 1970s (research by the Alliance for Childhood).

Whilst video games may offer many similar social and cognitive benefits to more traditional forms of play, they lack a crucial element: physical risk.

Researchers have identified 8 types of risky play:

Play with impact (such as repeatedly crashing into objects or the ground for fun)

Play near dangerous elements (such as playing near water, fire or cliffs)

Play at heights (climbing, jumping, hanging, balancing etc.)

Play with dangerous tools (ropes, hammers, knives etc.)

Play at high speed (running, sliding, cycling etc.)

Play with a chance of getting lost

Rough-and-tumble play

Risky play is so valuable for children’s development that the Canadian Pediatric Society wants to “shift the emphasis of children’s play toward greater risk-tolerance.” According to Dr. Mariana Brussoni, Director of Canada’s Human Early Learning Partnership:

“All children are naturally drawn and evolutionarily adapted to take risks through play. Driven by curiosity and excitement seeking, they learn about their environment, what it affords, how far they can push it and their own body, and how to manage the risks they encounter. Risky play can have wide-reaching benefits for children’s health, development, mental health and well-being.”

But risky play is disappearing. In 2008 I visited Petra. Whilst the red, rock-hewn architecture was incredible to see up close, it’s not what’s most indelibly imprinted on my memory of that day. The most remarkable thing I witnessed there amongst the sandstone mountains was a bevy of Bdoul* children playfully chasing one another across cliff edges, unbothered by the deadly 700ft drops. They can’t have been older than five, but were totally unsupervised.

It was momentarily alarming, but watching them move with such grace and joy, utterly at home in this awesome landscape, my heart quickly receded from my mouth. The contrast with my own childhood, though, and the bubble-wrapped lives of most Western kids, was dizzying.

*The Bdoul are a Bedoiun tribe who made a life at the Petra site for generations, but have been targeted by authorities in recent years.

This edition of Weirdness Wins is sponsored by Ideas On Acid — a forthcoming card deck of practices to reawaken your imagination and guide you towards the most adventurous corners of your mind.

I’m not saying everyone should start sending their kids off to frolic on cliff edges, but we’re also losing far more innocuous forms of play. A 2008 study by Play England found that half of all children In England had been stopped from climbing trees and 1 in 5 had been banned from playing conkers. This, I propose, is bonkers.

All this risk-aversion has serious consequences for how humans develop, and how society evolves. Researchers in Norway have suggested we should expect to see “increased neuroticism or psychopathology in society if children are hindered from partaking in age adequate risky play.” This might mean that measures like restricting or regulating social media, or banning smartphones for under-16s, are woefully inadequate ways to improve young people’s mental health (unless accompanied by a cultural reset around play).

But what about the effects on our collective imagination? Risky play encourages, amongst other things, a sense of independence and a comfort with uncertainty - two traits that are central to creativity. If we want to reverse the long-term decline of human creativity, parents, teachers, and governments must understand the value of risky play, and make more space for it.

What if adult life was less of a non-stop relentless grind?

For most grown-up humans, “play” is either something children do, or is associated with games. We play football. We play Scrabble. We play Grand Theft Auto. But how often do we approach life as play outside of these constrained and codified playgrounds?

The philosopher Alec Stubbs argues:

“We still experience the joy of play in adulthood, but only in moments that are few and far between. Even when we do play, it is seen as unserious or frivolous. In adulthood, play is taken to be nothing more than a short respite from work, a sojourn that helps us pass the time between periods of intense productivity.”

I’ve long believed that we do our best work when we approach it as play. In the words of German philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, “It is the joy in sheer creation, the dedication to the activity, the absorption in the movement, which transforms work into play.”

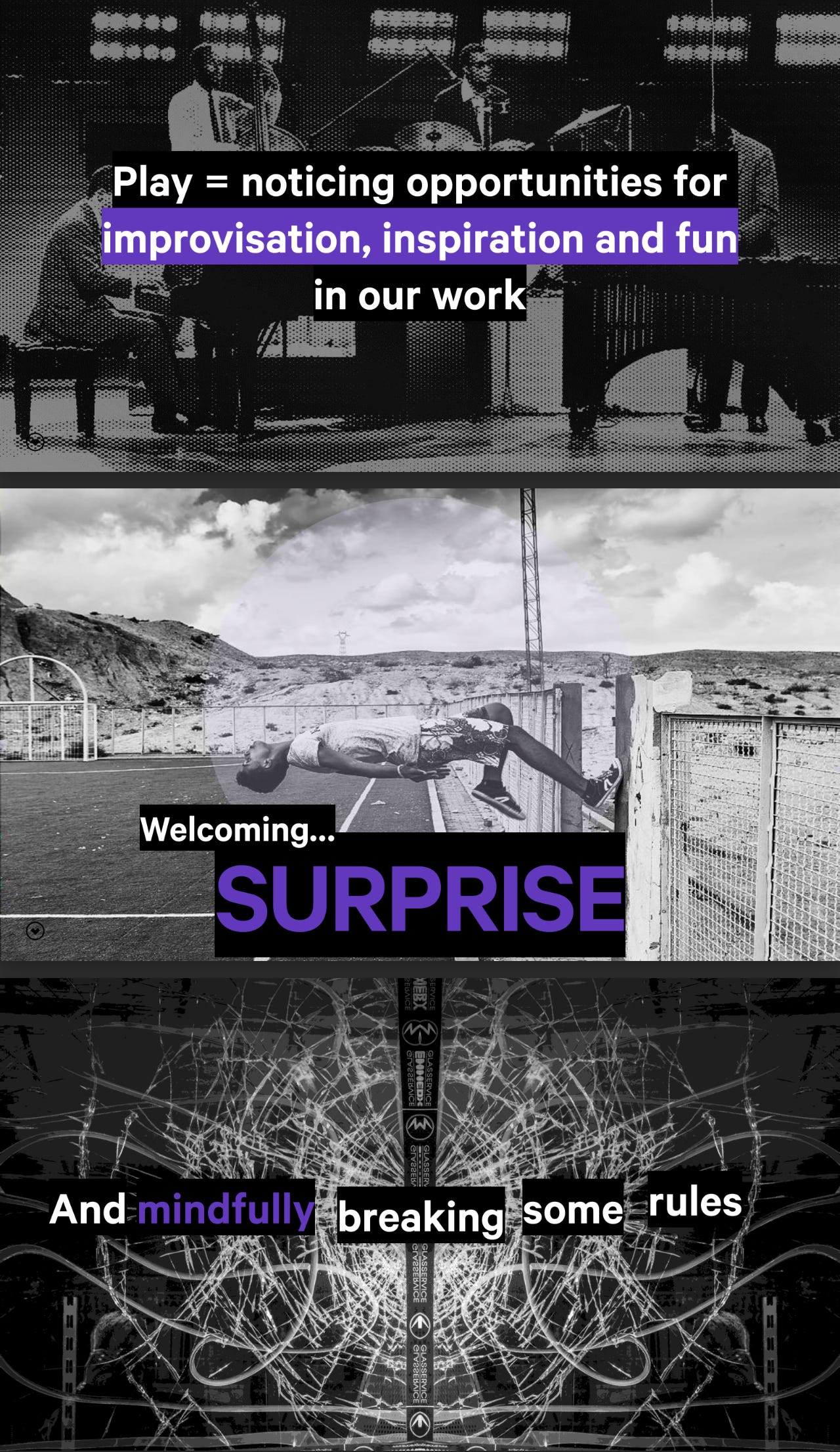

Methodically pursuing goals turns work into drudgery, transmuting what could be precious into something far more base. Attending to our work with a spirit of playful curiosity, and even a little mischief, is a very different experience. I ran a skillshare about the power of play back in my agency days, and settled on these three principles for work-as-play:

As the designer Rich Nadworny argues “We need time to try things when they don’t matter, we need practice stepping out of our competency into experimentation.”

But as Stubbs observes, all these injunctions to be more playful risk being toothless:

“It’s not just an act of personal rebellion but a social imperative. A call to playfulness is not an individual psychological prescription – it is a call to collective action against the achievement society.”

We’re talking about a paradigm shift, which demands that all of us who believe in the value of play must stand up for it, loudly, whenever and wherever we can.

Put simply, playing is a radical act. In his ‘Playful Manifesto’, Max Alexander writes:

“We live in a world where our value is so often defined by what we ‘produce’ or ‘contribute’. But we are so much more than that. Our productivity or our ability to be deemed useful by someone else is secondary. It doesn’t define us or determine our worth, but we are tricked into believing it does. The more we start to believe this, the less we play.”

Play powers progress

It’s hard not to instrumentalise play; to reduce it to a tool, something we can usefully deploy for some benefit beyond the act of play itself. The last thing I want to do with this piece is to frame play as another way to optimise your experience or the world at large. If you get to Sunday evening and find yourself fretting because you haven’t hit your target number of playtime hours this week, you’re probably doing it wrong.

But it would also be silly of me to ignore the contribution play has made, and can continue to make, to human progress. As the sociologist Yiannis Gabriel writes in his brilliant paper ‘Surprises: not just the spice of life but the source of knowledge’:

“Many discoveries of lasting significance come as a result of accident, serendipity and play. Such inquiry can be encouraged, both as a source of pleasure in its own right and as a potentially valuable source of ideas and innovation.”

This relationship between play and discovery is reflected in research with physics students:

“Giving students time for ‘messing about’, or exploring a physical system on their own – whether that’s in a lab, using computer simulations, or perhaps even through music – helps the students build an intuitive understanding of physics, which is demonstrated in their improvement in answering conceptual physics questions.”

Play also helps us adapt. The primatologist Isabel Behncke was the first person to publish scientific research about play behaviour in wild bonobos. Here’s what she says about the importance of play for humans:

“In order to adapt successfully to a changing world, we need to play. But will we make the most of our playfulness? Play is not frivolous. Play is essential… in times when it seems least appropriate to play, it might be… when it is most urgent.”

Our zeitgeist right now is flavoured by war, climate breakdown, and division. All of this is undeniably serious. And, of course, we’re in the biggest election year in history. Meanwhile, our business world is ruled by data and addicted to illusions of certainty. Playful, open-ended thinking often gets shut down.

In this climate, it’s hard to be the person who strolls in and says “what if we just… fart around?” But, like Behncke says, in this weird, scary moment, our future might just depend on it.

Stay tuned for the next essay in this Creative Renaissance series, where we’ll nerd out about the vital role of chaos.

Until then… keep it weird.

SECRET EXTRA BIT

Wow, you made it all the way to the end!

If you’re not a marketer, you’re free to go.

If you are a marketer, I have a small favour to ask…

Rob Estreitinho (author of the excellent Salmon Theory newsletter) and I are both big believers in the power of memes to capture and communicate truth. Seriously, most memes have more meaning crammed into them than your average 100-page PowerPoint horror-show.

Anyway, as well as our shared enthusiasm for memes, Rob and I both run workshops a lot with clients.

Recently, we had the wild idea of designing a workshop format for marketers where we use memes to figure things out together and align on decisions.

But this workshop could be so many different things. So we need your help narrowing the focus. Up for it? Here’s a super-short (like probably less than 60 seconds) survey we’re using to give us a bit of a steer:

Well said mate - literally, well written too. I've been making a concerted effort to fuck about more. Its a mental health imperative, to be honest.