Why chaos is good, actually

Chaos has an image problem. But without it, there's no creation at all.

“Chaos does not mean total disorder. Chaos means a multiplicity of possibilities.”

Jok Church, cartoonist

🦋🦋🦋

“Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void but out of chaos.”

Mary Shelley, novelist

👁️👁️👁️

“Chaos is what we've lost touch with… It is feared by the dominant archetype of our world, which is Ego, which clenches because its existence is defined in terms of control.”

Terence McKenna, ethnobotanist and mystic

Welcome to essay #2 in my Creative Renaissance series. If you’re new here, we’re exploring doorways to a more creative, more human future. You might like to read Is human creativity fading away? and Play as a portal to everything that matters most before getting stuck into this one.

Today’s theme is chaos.

At the first Chaos came to be

In Greek mythology, "Chaos" is the primal source from which everything originated. According to Hesiod's Theogony (a poem describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, written around 2,700 years ago), Chaos was the first thing to exist:

“Verily at the first Chaos came to be, but next wide-bosomed Earth, the ever-sure foundations of all the deathless ones who hold the peaks of snowy Olympus, and dim Tartarus in the depth of the wide-pathed Earth, and Eros (Love), fairest among the deathless gods, who unnerves the limbs and overcomes the mind and wise counsels of all gods and all men within them.”

In ancient Greek, the word "chaos" (Χάος) didn’t have today’s connotations of disorder and confusion. Depending on who you asked, Chaos was:

A void (or “chasm”)

Some sort of dwelling place

The female force of creation

The son of Chronos (the embodiment of linear time)

It was only around 700 years later, when the Roman poet Ovid described Chaos as "a shapeless heap" and "a rude and undeveloped mass" in his epic Metamorphoses, that we started associating the word with mayhem and mess.

Fast-forward to now, and a quick Google News search for “chaos” gives you an idea of how we’re conditioned to understand the word today:

I also asked the AI writing tool Claude to free associate from the word “chaos”. Here’s what it coughed up:

Disorder, confusion, mayhem, pandemonium, bedlam, turmoil, upheaval, frenzy, disarray, havoc, anarchy, entropy, unpredictability, randomness, messiness, disorganization, noise, madness, frenetic, unruly, wild, uncontrolled, unrestrained, unmanageable, turbulent, stormy, tempestuous, volatile, erratic, capricious, haphazard, helter-skelter, topsy-turvy, disheveled, jumbled, tangled, muddled, unkempt, frazzled, riotous, tumultuous, anarchic, lawless, chaotic systems, chaos theory, fractals, strange attractors, butterfly effect, sensitive dependence, bifurcations, dynamical systems, non-linear dynamics.

We’ve taken a word originally associated with the creation of all things and made it signify death, danger, decay, and intimidating, unfathomable complexity.

Chaos has become something to fear, not revere.

But what if some of its more recent associations - randomness, wildness, messiness, and even a little lawlessness - are in fact essential conditions for creativity? Perhaps these principles, rather than pulling us away from the original meaning of “chaos”, are exactly how we reclaim its ancient generative essence.

Embracing mess

In her book Bird by Bird: Instructions on Writing and Life, Annie Lamott says that “messes are the artist’s true friend.”

And in What is Philosophy?, Gilles Deleuze argues that it’s the job of artists and poets to slice through the normal parameters of thought and “let in a bit of free and windy chaos”:

But this essay isn’t just about art. We’re talking about creativity in all human domains.

In the words of the organisational theorist Ralph Stacey, “mess is the material from which life and creativity are built.” This is echoed by the Nobel prize-winning chemist Ilya Prigogine in his book Order Out of Chaos; our physical world, he shows, “is a world of instability and fluctuations, which are ultimately responsible for the amazing richness of forms and structures we see in nature around us.”

In both the evolution of life and the evolution of ideas, mess has been a key catalyst. As Steven Johnson explores in his book Where Good Ideas Come From, innovation, despite the word’s gleaming technical sheen, often emerges “on the brink of chaos, in the fruitful realm between order and anarchy.”

The coffeehouses of 17th and 18th century Europe are a great example of how a little disorder can fuel progress. These coffeehouses were places where scientists, poets, politicians, and businessmen gathered and exchanged ideas. The informal environment and eclectic mix of people encouraged cross-pollination of ideas and radical thinking.

Coffeehouses were so revolutionary, in fact, that in 1675, England’s King Charles II issued a proclamation to close them. The backlash was so strong that just a few days later he revoked the order. The open discussion he feared led to an “explosion of new ideas” during the Enlightenment. Isaac Newton even dissected a dolphin on a table at the Grecian Coffee House near Fleet Street one day. Mad lad.

The immense usefulness of deep confusion

The organisational consultant and writer Margaret Wheatley talks about “order on the other side of chaos”. In organisations, for Wheatley, “chaos” is when people are confused, overwhelmed by information, and unsure what to do next. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing! In her words:

“The first task, when chaos erupts, is not to shut it down, not to reach for early closure, not to immediately move back to our past comfort level. At those moments, what people do not need is for someone else to come in and make sense of it all for them. Nor do they need the other normal strategy, which is to back away from all of this information and just work a piece of it. What they need instead are processes by which they can stay with the discomfort… long enough that they get knocked off their certainty, long enough for them to reach the clarity that they no longer know what works, that their model, their frame for organising this problem or this organisation doesn't work any more.”

Deep confusion is a doorway. On the other side, new ways of thinking and new ideas. Or as Wheatley’s written elsewhere, “The things we fear most in organisations – fluctuations, disturbances, imbalances – are the primary sources of creativity.”

Alex Smith - author of No Bullshit Strategy and one of the most exciting thinkers in the strategy space today - frames the act of strategy in precisely this way:

“Many intuitively understand strategy to be a "risk mitigation" discipline, that seeks to bring order and control to chaos, but it's actually the opposite of that.

Strategy seeks to *generate* chaos.

Unpredictability.

Jeopardy.

It's your way of breaking from the passive well-trodden path that the world is funnelling you down, and forging one that's totally new.”

This openness to chaos doesn’t come naturally to most. “Let’s make things less predictable” isn’t what your average executive or business owner wants to hear. Neither would it make a particularly persuasive campaign slogan for a political party. But that just tells you how far away we are, culturally, from accepting and internalising the true nature of progress.

Making friends with uncertainty

It’s beyond cliché in 2024 to say that we live in uncertain times. The truth, of course, is that there were never certain times. The world, despite all our intellectual advances, remains stubbornly unpredictable, especially when humans are involved.

The drive to impose order runs deep. We’re pattern-hungry creatures, eager to feel in control. These ancient habits of mind manifest today all kinds of ways. Sometimes it’s pantry organisation videos getting millions of views on TikTok. Sometimes it’s conspiracy theories offering our most alienated individuals the intoxicating illusion of everything finally making sense. But no matter how firm your beliefs, or how perfectly you store your spaghetti, the endless swirl of uncertainty remains.

Rather than repressing this fact, or trying even harder to exert control, we have another choice: Cultivating (and modelling) a more open and improvisational attitude. We can become chaos-surfers.

This is basically a Stoic perspective: “If you are relaxed and expect change, then you can deal with it better.” But accepting uncertainty doesn’t mean we’re simply victims of chance, reacting to life as best we can. In the words of the political scientist Brian Klass:

“We control nothing, but we influence everything. As chaos theory proves, in an intertwined system, every action has an unforeseen ripple effect. Nothing is meaningless. And that yields a profound truth: that everything we do matters.”

Dougald Hine, author of At Work in the Ruins, talks about “affecting the conditions of possibility,” rather than seeking control. This more ecological way of thinking invites us to dance with emergence, instead of imposing rules and processes on others (or, perhaps, ourselves).

A new age of adaptability?

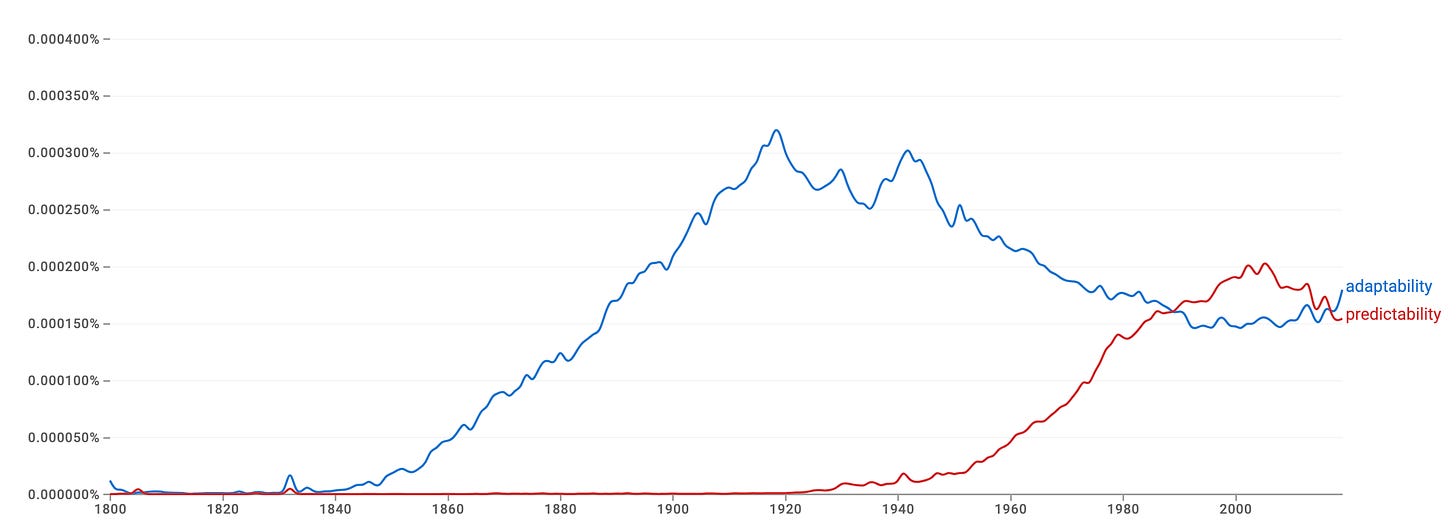

This graph - from Google Ngram Viewer - shows how often the words ‘adaptability’ and ‘predictability’ have occurred over the last couple of centuries in a corpus of over 15 million books.

There are lots of stories you could wrap around this data, but the way I’m reading it is that we’ve reached the peak of inflated expectations around just how predictable we can make the world with all our technology and data and planning.

‘Adaptability’ seems to have been a more widely-discussed, and perhaps widely-respected, human value in the past, peaking just as the industrial-grade horror of WWI arrived. After a 100-year decline, ‘adaptability’ has recently pulled back in front of ‘predictability’. Might the coming years and decades see us reorient our systems, and our souls, towards more adaptive, flexible, resilient ways of being?

When I asked my custom GPT - Deep, yo - to comment on this data, it offered this:

”It reflects a move from hubris to humility, acknowledging that the human condition is defined not by mastery over nature, but by an ongoing negotiation with a world that eludes totalisation. The rise of adaptability speaks to an era where change is the only constant, and our survival depends not on our ability to predict the future, but to remain fluid, resilient, and responsive to the unforeseen. The real work lies not just in adapting within the systems but transforming the systems themselves for a more equitable future. This is the hidden beauty in our tumultuous times: the continuous unfolding of human capacity to generate new forms of life and meaning out of the very disruptions we face.”

Deep, yo.

Exiting your reality tunnel

We

are a tribe

of philosophers, theologians,

magicians, scientists,

artists, clowns,

and similar maniacs

who are intrigued

with

ERIS

GODDESS OF CONFUSION

and with

Her

Doings

— Greg Hill and Kerry Wendell Thornley, Principa Discordia

The words above are from the first published text of the maybe-but-not-entirely-satirical religion, Discordianism. This ‘religion’ seems to have mutated from an absurdist joke conceived in the late 1950s into a meaningful, if elusive and shape-shifting, worldview.

For Discordians, “neither order nor disorder really exists, but they are concepts that enable humans to deal with reality, which is chaos.”

Here’s another snippet from the Principia Discordia.

“Pick a grid, and through it some chaos appears ordered and some appears disordered. Pick another grid, and the same chaos will appear differently ordered and disordered.

Reality is the original Rorschach.”

What do you see above? I see the moment just before a baby is born.

But your Rorschach - and your reality tunnel - may differ.

What if we could “relax our tiny tunnel of perception and let it expand like a mother giving birth?” asks the artist and Embodied Imagination practitioner Pamela Holmes.

How might we achieve that expansion? In future essays in this series, we’ll explore the role of daydreaming, meditation, and psychedelics. Art, and poetry, as our Deleuze puppet argued above, are also powerful conduits for looser, freer states of consciousness.

There are also creators operating in the edge-lands between artistic and reportorial forms of media, like the documentary-maker Adam Curtis, who, by engaging with our chaotic contemporary condition, can perhaps help us appreciate the fresh possibilities it contains.

Reacting to Curtis’ 2016 film HyperNormalisation a year after its release, Trey Taylor suggested that:

“Curtis achieves a sense of dream-like removal. This lets us absorb the meta narrative without becoming a part of it… This detachment is necessary for achieving change… We must be able to step back and grasp the whole of this dynamic societal tableau, otherwise visions for radical change are inhibited by a deep, dogmatic involvement in the present.”

We are, as Perspectiva’s Jonathan Rowson writes, “in a time between worlds”. A time where our creative powers seem to be disappearing and our climate is spiralling away from the stability we’ve long enjoyed. A time where disorder and destruction seem to reign. But also a liminal moment where what comes next could, if we surf the chaos just right, be beautifully, utterly alive.

“From the current destructive chaos, we can move on to generative chaos… a new way of being and inhabiting planet Earth.”

Leonardo Boff, theologian and philosopher

🦋👁️🦋

“Humans have a radical creative responsibility for their individual and collective lives… We’ll get the future we imagine, not necessarily the one we deserve.”

Take a trip to Thinkytown

This edition of Weirdness Wins is sponsored by Ideas On Acid - a forthcoming card deck by ME!

Ideas On Acid is a set of 50 practices and techniques designed to activate your imagination and help you build a future worth getting excited about.

Join the waitlist for early access and a juicy discount 👇

Thanks for reading, and please, more than almost anything, remember to keep it weird x

Chaos is EVERYTHING. I adore it.

love this, and look forward to the rest of the series