It’s been a while since my last post. In fact, it’s the longest gap I’ve allowed myself since I started this Substack just over a year ago.

Reasons include:

Getting Covid

Dealing with some stressful legal stuff

Moving out of our house in Manchester and beginning a more nomadic existence (I’ll probably write more about this soon)

But maybe my radio silence wasn’t such a bad thing. Maybe your inbox was already overstuffed enough. Maybe it’s absolutely fine — healthy, even — to go weeks, or months, without saying anything at all.

Which brings me to the subject of today’s essay (the third in my Creative Renaissance series). So far, we’ve explored the power of play and the generative potential of chaos. Now, it’s time to consider the virtues of quiet.

NOTE: This is a long post. Your email app might truncate it. Click here to read it in your browser.

We’re not built for this much noise

Humans evolved in relatively quiet environments, with sound playing a crucial role in survival. Our auditory system developed to detect and localise sounds quickly so we didn’t miss threats like a nearby bear or a falling rock.

Noise activates stress responses via the sympathetic nervous system (which produces our “fight or flight” response) and something called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (a communication system that connects various hormone-releasing bits of our anatomy). These responses were adaptive in our distant past, but, when they’re chronically activated, they mess us up.

Indeed, noise pollution is emerging as a major public health concern globally. According to the World Health Organisation, noise is the second biggest environmental cause of health problems (air pollution is the first). When it comes to quality of life and mental health, noise does more damage than smog. Living in a noisy environment makes it harder to focus, harder to relax, and harder to sleep.

Whilst low-level ambient noise can enhance creativity for some people, research has shown that, at 85 decibels and above, noise impairs creative thinking — think heavy city traffic or someone vacuuming nearby. Another study found that open-plan office noise negatively impacted workers’ memory, energy, and motivation.

Noise also surrounds us in more figurative forms. Global news whooshes in and out of view at gale-force speeds. Memes spawn, spread, and fade in the fibre-optic blink of a screen-burned eye. More than 40 million WhatsApp messages are sent every minute.

The amount of information in the world is increasing exponentially, now accelerated by AI. But our ability to process information remains largely unchanged; we have an upper limit of processing around 126 bits of information per second.

Living in an informational atmosphere so thick with cognitive pollution has all sorts of real-world effects. In 2022, 80% of global workers reported experiencing information overload, up from 60% in 2020. And economists estimate that this all comes at a global cost of around $1 trillion.

“Information overload can have severe implications. It begins by eroding our emotional health, job performance, and satisfaction, subsequently influencing the actions of groups and ultimately, entire societies.”

— Dr. Curt Breneman, Dean of the School of Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

There’s a disorienting quality to all this noise, which is fitting, really, given the word ‘noise’ comes originally from the Greek ‘nausia’, meaning seasickness.

Around 1,600 years before that word entered usage, ancient Mesopotamian scribes engraved The Epic of Gilgamesh into clay tablets. In this epic poem — one of the oldest known literary works — the deities grew so tired of the noise of humanity disturbing their sleep that they sent a great flood to wipe us all out.

Now, perhaps, the noise and the flood are one. We’re drowning in content slop and disappearing into one bottomless algorithmic vortex after another, all of which bathes us in dopamine whilst bleeding our attentional capacities dry.

As Mr. Rogers once put it, “our society is much more concerned with information than wonder.”

If we’re serious about arresting the decline in human creativity, we must reacquaint ourselves with silence and stillness. We must find ways to escape the deafening and disorienting roar. We must carve out quiet moments so new ideas and insights can whisper their way through the cracks.

Why does quiet freak us out so much?

Noise may overwhelm us, but cutting it out isn’t as simple as it might seem. I’m by no means the first person to point out that silence weirds us out. Like darkness, there’s something about it that disturbs us on a primal level.

True silence is something we almost never encounter in daily life (despite the sounds of the natural world disappearing at an alarming rate). Even most people who are deaf have some auditory perception. The closest most people with healthy hearing get might be a meditation retreat or a spell in solitary confinement. A select few get to experience an anechoic chamber.

It’s impossible to entirely untangle silence from notions of nothingness, psychosis, and death. Silence forces a confrontation with the self. It demands an acceptance of emptiness. It strips us of everything we usually rely on to drown out the existential dread — that stubborn undercurrent of all human life.

When you combine all that with the unending availability of diversion and distraction in our contemporary techno-social milieu, it’s hardly surprising if we feel a deep-seated aversion to quiet. But it seems clear that’s not serving us.

“All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

— Blaise Pascal (1623 - 1662), French mathematician, physicist, inventor and philosopher

Phronemophobia: The fear of thinking

In 2014, Wilson et al. published the results of 11 studies investigating how people behave when forced to simply sit and think. They found that many people (especially men) “preferred to administer electric shocks to themselves instead of being left alone with their thoughts.” Even in familiar, comfortable environments like home, people struggled to enjoy periods of just… thinking.

The quiet asks us to listen to the inner questions that only silence can pose. Perhaps the fear of thinking is also a fear of freedom; the freedom to redefine ourselves and create something truly new.

The modern pressure to continually process, produce, and perform

As

wrote recently, “the modern world tells us to get out there and promote ourselves.” Where “ancient wisdom speaks to the power of retreat,” he notes, in contemporary life “we’re compelled to fill the void of the market rather than explore the void within.”In a 2023 episode of the podcast How to Keep Time, Becca Rashid laments how “all those emails and texts and posts and notifications give us more stuff we can do… That makes it harder to tolerate wasting time — just doing nothing, or being alone with your thoughts.” Later, she adds that “we’re either anxiously planning for the next task, or we’re being compulsively productive because we’re sort of nervous about free time.”

of calls this free time “blank time”:“Even before the pandemic, we were so obsessed with the performance of productivity (meetings, of course, plus myriad other ways of LARPing your job) that most workers had very little blank time in their days. And as the sheer number of meetings (and messaging) has increased, that small amount of blank space has decreased even further.”

Chronophobia: The intense and persistent fear of time passing

Yep, chronophobia: that’s a second obscure fear you can add to your dinner party trivia bank.

We might best understand the urge to surrender to busyness as a subconscious attempt to delay our own inevitable demise. Filling our days with noisy task-completion (rather than letting them be empty and quiet) lets us feel like we’re mastering time. The relentless passage of time is harder to ignore when you’re quietly doing nothing much at all.

To be supremely comfortable with quiet means being content feeling unproductive; learning to luxuriate in the void, curious about the secrets that might lurk within.

Making space for stillness and boredom

Here’s a crude summary of the ground we’ve covered so far:

The noisiness of the world (both literal and figurative) comes with serious costs, affecting how we feel and think

Shutting out the noise isn’t necessarily straightforward, because of our psychology, our technology, and our cultural conditioning

In this section, we’ll explore why that struggle is nevertheless worthwhile. We’ll see where ancient traditions mesh with modern scientific and philosophical thought in revealing the spiritual and creative rewards that quiet, stillness, and boredom can provide.

Perhaps ironically, given its word count, this essay is a celebration of what

calls “the ancient mystical practice of doing nothing”. This practice has various nuances and expressions across time and space.‘Dadirri’, for example, is an Australian Aboriginal practice, particularly associated with the Ngangikurungkurr people of the Daly River region. Dadirri means “inner, deep listening and quiet, still awareness.” Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr, a member of the Ngangikurungkurr tribe (which means “deep water sounds”, or “sounds of the deep”), describes how:

“My people are not threatened by silence. They are completely at home in it. They have lived for thousands of years with Nature’s quietness. My people today, recognise and experience in this quietness, the great Life-Giving Spirit…

Our Aboriginal culture has taught us to be still and to wait. We do not try to hurry things up. We let them follow their natural course – like the seasons. We watch the moon in each of its phases. We wait for the rain to fill our rivers and water the thirsty earth…To be still brings peace – and it brings understanding. When we are really still in the bush, we concentrate. We are aware of the anthills and the turtles and the water lilies.”

Stillness lets us notice things we might otherwise miss. It gives us the space to respond more creatively to the unfolding now.

“Attention changes what kind of a thing comes into being for us: in that way it changes the world.”

— Dr. Iain McGilchrist, psychiatrist, neuroscientist, and philosopher

For most of us in the West, this habitual, silent waiting, listening, and observing is an alien way of life. We’re deeply uncomfortable with boredom. Our philosophers have long denounced this barren state of being. For Kierkegaard, boredom was the root of all evil, and Sartre called boredom, rather evocatively, a “leprosy of the soul.” More recently, the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm claimed boredom was “perhaps the most important source of aggression and destructiveness today.”

There’s likely some truth in this. Chronically bored people are probably more open to conspiracy theories and extremist ideas. But that doesn’t mean we should throw the boredom-baby out with the boring bathwater. Personally, I prefer Bertrand Russell’s take. In his 1930 book The Conquest of Happiness, he wrote that "boredom is… a vital problem for the moralist, since at least half the sins of mankind are caused by the fear of it." Writing around the same time, Walter Benjamin went even further, arguing that “boredom is the threshold to great deeds.”

Boredom as the prelude to brilliance? The science increasingly supports this view:

“When volunteers are forced to do mind-numbing repetitive tasks or listen to agonisingly dull lectures for short intervals, their scores on standard tests of creativity rise substantially directly after.”

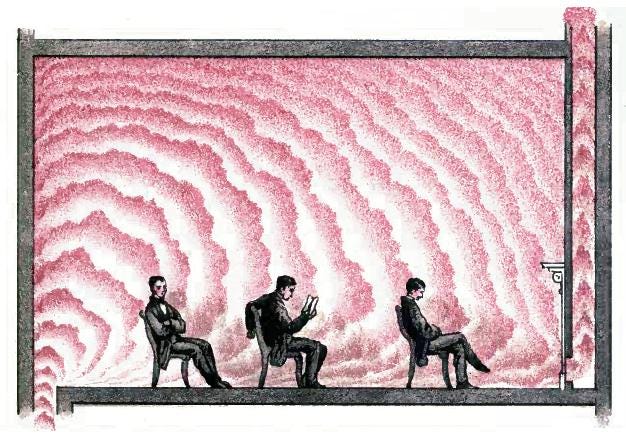

The American neuroscientist and neuropsychiatrist Dr. Nancy C Andreasen, inspired by the habits of highly-creative individuals, conducted a brain-imaging study to explore the neural basis of what she calls "free-floating periods of thought." These periods varied among creatives: Leonardo da Vinci would sit for hours contemplating a painting, while Einstein preferred drifting aimlessly in his boat, "Tinef" (Yiddish for “piece of junk”), often requiring rescue.

Andreasen's study revealed that during these "resting states," the brain is far from passive, showing activations in multiple regions of the association cortex. This state, termed REST (random episodic silent thinking), engages the brain's most complex areas, gathering and linking information in potentially novel ways. Andreasen's findings suggest that the brain defaults to creativity when given the opportunity to wander freely, highlighting the value of incorporating such periods into our daily routines.

The writer and activist Rob Hopkins (author of The Ministry of Imagination Manifesto), describes how quiet connects us to nature, the cosmos, and ourselves, and sees this as essential preparation for imaginative, world-changing work:

“Imagination can come in a flash of insight, but that flash of insight occurs in a field that’s been prepared, and the preparation for that field is oftentimes solitude, is quiet, is reflection, is contemplation. When we’re talking about our imagination, that’s connected to the cosmos, that’s connected to the planet. The voices of the cosmos and the planet are persistent and powerful, but they can be overwhelmed by the voices of technology and the voices of society and the daily din of activity and noise and clutter… Mentally and psychically… we can’t respond to the most subtle voices of our psyche and our soul and our unconscious when we’re constantly being titillated and distracted.”

If this all sounds a bit too abstract, let’s bring it back down to Earth for a moment. As Austin Kleon writes in Steal Like an Artist:

“If you’re out of ideas, wash the dishes. Take a really long walk. Stare at a spot on the wall for as long as you can… Take time to mess around. Get lost. Wander. You never know where it’s going to lead you.”

Slowness and silence as radical acts

“Silence is the only phenomenon today that is ‘useless.’ It does not fit into the world of profit and utility; it simply is. It seems to have no other purpose; it cannot be exploited… It makes things whole again, by taking them back from the world of dissipation into the world of wholeness. It gives things something of its own holy uselessness; for that is what silence itself is: holy uselessness.”

— Max Picard (1888 - 1965), Swiss writer and philosopher

As much as I appreciate this quote, I’d argue silence isn’t the only thing that’s sacred by virtue of its resistance to the logic of the market. Play (for its own sake) has a similar kind of “holy uselessness”, as I explored in an earlier essay. But I love the idea that there’s something subversive about simply being quiet.

In his newsletter —

— recently coined the term ‘slowpunk’ to capture this idea and explore how it’s manifesting in culture right now:“Forget the aggressive and distorted sound of Sex Pistols, Black Flag and Bad Brains. If you want to fight the system, instead you have to keep quiet and listen for the sounds of birdcalls, whispers and rustling leaves. The weirdos and skaters are no longer interested in shouting obscenities and smashing windows, instead they want to leave their phones at home, be present and touch grass…

Joining the slowpunk movement can take many forms. Sometimes it’s about escaping the rat race and resisting the urge to rush forward. Sometimes it’s a complete identity shift. Sometimes it’s smaller acts of resistance, like turning off your app notifications. But fighting through the collective fear of being left behind - going slower than everyone else - is never easy. That’s the nature of being a punk; it’s a commitment to take a stand and risk societal rejection. That’s what it takes to fight for your right to stand still and enjoy life at a slower pace.”

Silence also has a strange kind of magic as a tool of political protest:

In the early 20th century, the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People organised several silent marches to protest racial injustice, most notably the 1917 Silent Parade in New York City.

In 2013 during the Gezi Park protests in Turkey, performance artist Erdem Gündüz stood silently in Taksim Square for hours, inspiring others to join in silent standing protests.

In 2018, Parkland high school shooting survivor Emma Gonzalez paused for 6m 20s in the middle of her speech at the March for Our Lives — the precise amount of time it took a gunman to kill 17 people at her school. Franklin Leonard, founder of The Black List, called it “one of the most remarkable political moments” he’d ever seen.

If you’re trying to change the world at literally any scale, quiet is your friend. In this age of noise, quiet’s power is clear both as a private practice and as a public statement.

Don’t just do something — sit there!

Great thinkers have been nudging us away from noise for a long time, but the sound and light of our cities and screens have proven impossible to resist.

Lao Tzu said “silence is a source of great strength”; 1 billion active monthly TikTok users seem to disagree. Plutarch said “silence at the proper season is wisdom, and better than any speech.” I guess Donald Trump didn’t get the message. But it’s never too late to rediscover what the ancients understood.

We glimpsed a quieter world when Covid hit. My mornings were blanketed by birdsong, unobstructed by the evolutionarily-triggering engine-growls of the usually crowded roads below my window. For me, this was a period that reignited my love of long-form writing. It was a time for sketching trippy self-portraits and photographing the eery emptiness on my approved daily walks. Maybe the weekly British ritual of clapping for the NHS was an instinctive reaction against the involuntary noiselessness of this strange moment. But amidst the weirdness, there were hints of different ways of being. There was an otherwordly spaciousness about those early Pandemic days, and for all the tragedy and folly of that chapter in the human story, it did briefly reveal something profoundly important that we should do our best to protect.

What might you hear if you turned down the volume of the world? What ideas are waiting in the spaces between your tasks? What change might ripple outward from a quiet rebellion against the endless noise?